Decomposing the Star of David

by Victoria Shingleton

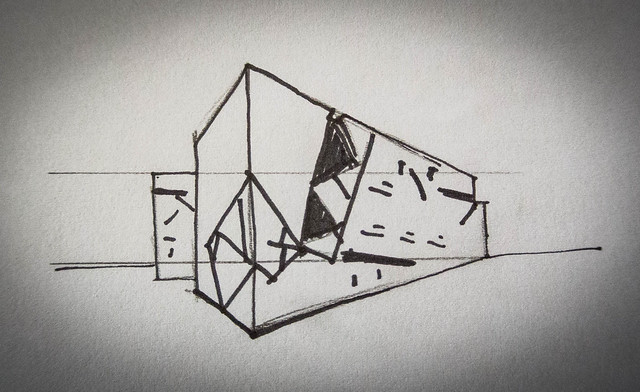

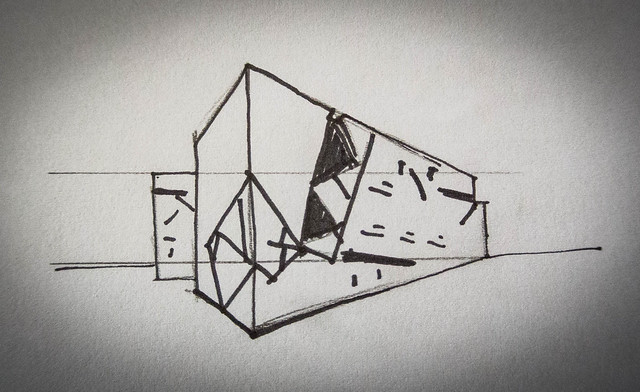

When I first saw Daniel Libeskind's Jewish Museum in Berlin, I was intrigued not only by the harsh angles and zig-zagging mass of the building, but also by the irregularity of the exterior surface. Voids in the facade of the building are cut with seemingly random, sharp punctures, almost as if the skin itself was scarred. Libeskind's building is completely metaphorical, intended to evoke feelings that the Jewish population of Berlin felt after World War II. I wanted to further explore the metaphorical and emotional qualities that Libeskind used to create the experience.

|

| Sketch of Libeskind's Jewish Museum in Berlin |

The voids in exterior skin, while random, are uninterrupted - as if the angles which form the sharp edges of the building do not exist. If you flatten out the facade of the building, the sides appear as a continuous surface. It is difficult to tell where the skin folds into zig-zagging angles, as well as where they would fit in relation to the plan. It is almost as if Libeskind cut into a continuous strip of paper and then folded it around his plan.

|

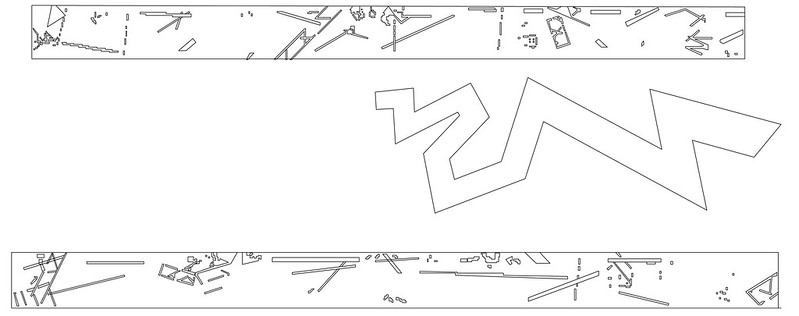

| Though punctured, the facade is continuous. |

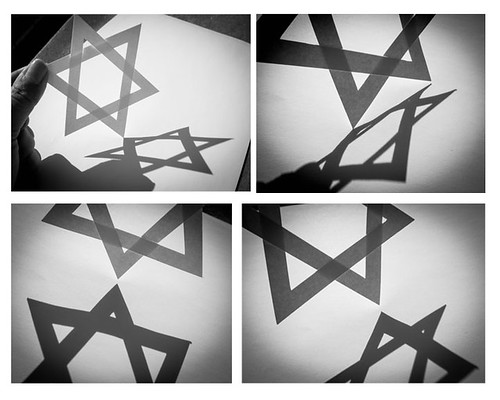

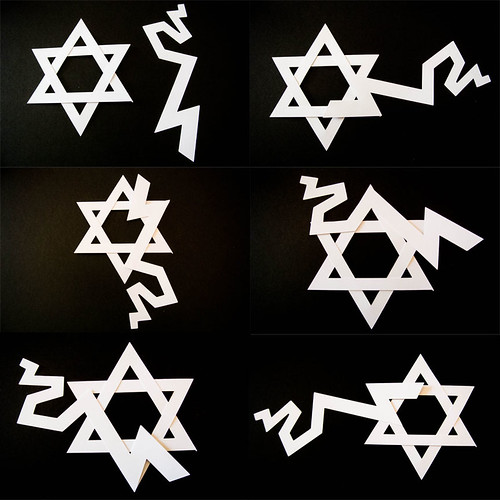

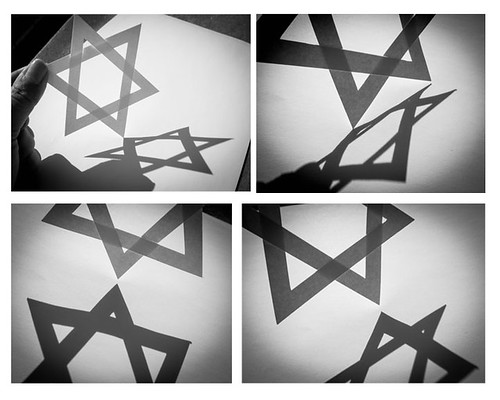

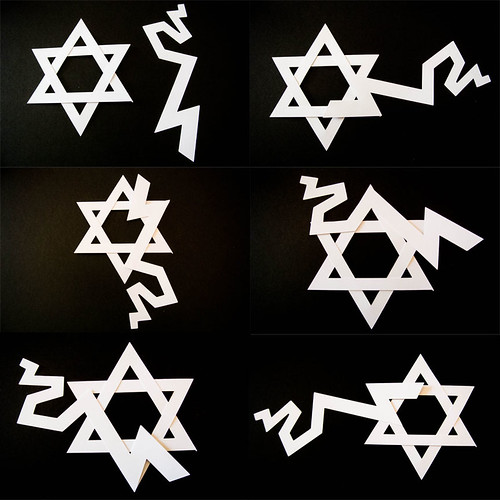

It has been suggested that Libeskind used a loose interpretation of the Star of David, a Jewish symbol, to form the irregular angles of the voids of the museum's skin. I decided to use light and shadow to further explore this idea in attempt to gain a stronger understanding of the meaning behind the punctures.

|

| Shadow Study: Star of David |

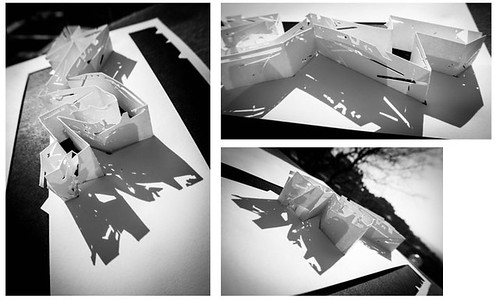

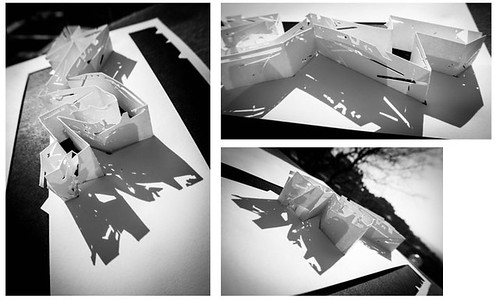

By comparing the shadow produced by the Star of David to the shadow produced by the voids of the museum's facade, I could begin to see how the angles of the cuts of the facades could be construed from angles of the Star of David. However, I believe that the voids can also serve as a metaphor for the permanent marks left on the Jewish population of Berlin after WWII. And while the voids appear on the surface of the building as darkness, I couldn't help but notice that the shadows produced by the paper fabrication left exactly the opposite - light - perhaps indicating that even in the darkest of times, even the smallest trace of light can provide a glimmer of hope.

|

| Shadow Study: Libeskind's Jewish Museum |

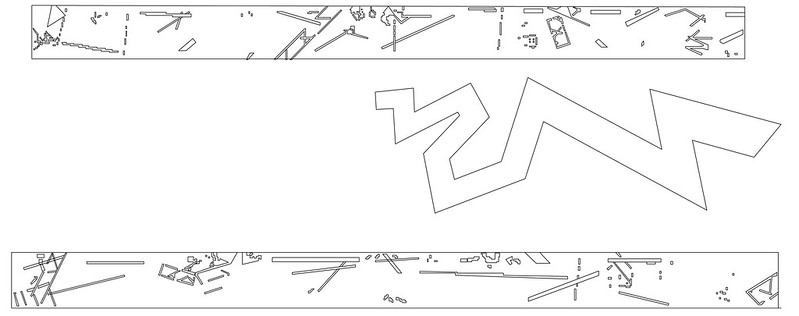

The zig-zagging plan of the building was said to be based upon the deconstruction of the Star of David. To further understand this method, I used the symmetrical and regular geometry of the Star of David and physically arranged it with the asymmetrical and irregular geometry of the plan of the Jewish Museum.

|

| Geometry Study: Star of David v. Jewish Museum Plan |

While there may be similar angles and proportions of the Star of David in relation to the plan of the building, most apparent in the sharp angles can provide symbolic meaning to the plan, there may be a stronger relation within the confusion and disorientation the guests must feel in the irregular layout of the museum, similar to how lost and afraid the Jewish population must have felt before, during, and after WWII.

Whether or not the Star of David is visually present in Daniel Libeskind's design of the Jewish Museum in Berlin can really only be determined by the observer. However, whether or not the user can see the star, I believe it is nearly impossible to ignore the many metaphorical values present in Libeskind's design. It isn't a building constructed to be beautiful - it's a building constructed to evoke emotion. And whether that emotion is fear, hatred, confusion, or scorn is simply in the eye of the beholder.

.jpg)

.JPG)